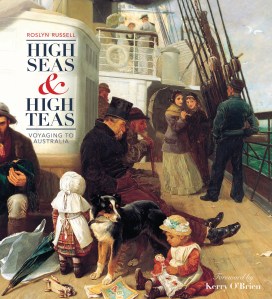

High Seas & High Teas: Voyaging to Australia

213 P & notes, 2016, NLA Publishing

With the recent emphasis on ‘illegal boat arrivals’ in Australia in recent years, it has often been pointed out that, with the exception of indigenous Australians and families who arrived within the last sixty years, all Australians come from ‘boat people’ stock. Rustle the branches of most family trees and there they are: the names of ships, the point and date of departure and the point and date of arrival. Turn to page 2 of the Port Phillip newspapers during the 1840s and there’s the shipping news, identifying the first class passengers by name, numbering the second class passengers, and dispensing with the rest as an undifferentiated group of ‘bounty migrants’ or ‘steerage passengers’.

The inside blurb of this book exhorts family historians to “get a sense of your ancestors’ shipboard experience”, and the foreword by Kerry O’Brien centres on his own family lineage reflecting somewhat of a ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ emphasis. Family historians often have little more than the name of the ship and its departure and arrival dates of their forebears. Sometimes they are fortunate enough to have a diary or letters penned on the journey, or on occasion, a particular trip may be so notorious that it was subjected to the scrutiny of the authorities afterwards. In all these cases,though, there are broader questions in moving from the particular to the general: how typical was this one trip? Is there a commonality of experience that linked all sea journeys to Australia?

Roslyn Russell fleshes out and contextualizes the voyage between embarkation and arrival in her book High Seas & High Teas by drawing on thirty-three diaries penned by passengers and crew during the nineteenth century. These diaries, chosen from among the 100 accounts of voyages to Australia held in the Manuscripts Collection of the National Library of Australia, are not necessarily an accurate reflection of the demographic makeup of ships’ passengers. As she points out both in her introduction and at other places in the text, most of the diaries are written by men (roughly three to one) and fourteen of the thirty-three diaries were written by first class passengers. The voices of mothers of young children, in particular, are missing. This imbalance, she suggests, may be explained by social factors, but it could also reflect the collecting interests of the enigmatic Rex Nan Kivell and Sir John Ferguson, whose collections formed the basis of the NLA holdings (p.2).

In her brief introduction, she explains that, over time, three main routes were established between Great Britain and Australia. Most early 19th journeys took the High Seas route down to the coast of South America, sometimes stopping at Rio de Janeiro, then across to Africa and down to the south of the Cape of Good Hope and on to Western Australia, Adelaide, Melbourne or Sydney. From the 1830s an alternative route opened up when passengers travelled across the Mediterranean by steamship to Cairo; by camel and cart to Suez, and by steamship again to Bombay. There they connected with sailing ships that brought them down through Torres Strait. By the 1850s a third, more dangerous route was developed when clipper ships passed far to the south of the Cape of Good Hope to pick up the Roaring Forties, the strong winds that blew between 40-50 degrees S latitude, which yielded a shorter journey but also risked storms and icebergs. Steamships were introduced to the route from the 1850s onwards, and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 cut the length of the journey from more than 100 days in the early 19th century to 40-50 days by the 1890s.

Despite these technological and itinerary changes, there was a commonality to the experience of the sea-voyage, just as there is a basic underlying sameness about air travel today. This commonality even extended to the convict ships which plied the oceans until the 1860s. Russell has devoted the first chapter to ‘Sailing Under Servitude’, where the surgeon-superintendent played an ambiguous role encompassing both solicitude and discipline. Diary entries in this chapter from crew and surgeons underscore the isolation and fear of insubordination that ran as an undertone throughout the journey, but as her references to convict ships in the later thematic chapters of the book demonstrate, even convict ships experienced the same combination of boredom, fear, discomfort and self-made amusement that marked the journeys of later passengers of all classes for the next century.

Chapters 2-12 follow the trajectory of the journey from embarkation at port and the often lengthy bureaucratic and nautical delays before actually setting sail (Ch.2); the provisioning and accommodation on board (Ch. 3-5); passing the time (Ch.6-9); misfortunes at sea (Ch. 10-11), and the final arrival at their destination (Ch.12) which could, once again, be delayed by bureaucracy and quarantine requirements. I was surprised to learn of the emigration depots back in England which acted as a sort of on-land simulation of the steerage experience, with emigrants forced to sleep in dormitories and comply with Royal Navy regulations as a way of familiarizing them with the life that faced them for the next four or five months. I had seen printed newspapers purporting to be written on board ship and wondered at how they were published. Russell explains that they were hand-written on board ship and, after a subscription was collected from the passengers, the funds were put towards publishing the newspaper on land, after arrival, as a memento. Like Russell, I had wondered about sanitary arrangements- a topic which, unfortunately, few diary-writers explored in much detail.

But the real heart and soul of this book is the diaries. Each chapter commences with a potted biography and then a transcript of one person’s diary that illustrates the theme of the chapter, followed by a beautifully clear, double-paged image of that page of the diary. As readers, we encounter the diary writers again in several places, and I came to look forward to Annie Gratton’s (1858) and Edith Gedge’s (1888) vivacious entries, and confess to a twinge of schadenfreude at the sour William Bethell’s whinges and complaints. Some diarists reappear often, while others have a fleeting presence, making highly pertinent observations, then disappearing into the throng of passengers again.

The book is lavishly illustrated with the small sketches that the diary-writers used to embellish their pages and the chapters are enhanced by artworks of the day described as ‘background features’ in the reference section at the back. It really is a beautiful book to just dip into, with large, full colour illustrations on nearly every page.

I’m not aware that the book is part of any museum exhibition, but as a reader, I felt as if I were viewing a mounted display. The trajectory of the journey provided a narrative spine, branching off into small sub-themes of just two pages in length, just as a museum display might do. Overall, the book does not have a historical argument as such- except, perhaps, for the commonality of the voyage experience across time and class- but instead brings the journey to life through images and the voices of the diary-writers.

It was probably because I had become comfortable with the chatter of those voices that the ending seemed so abrupt. Mr W. Barringer, with whom she closes, moves into permanent accommodation and the book ends. I would have welcomed Russell onto the stage herself as author or researcher perhaps, or would have liked the book rounded off with a birds-eye view of the voyage experience more generally, or even just a fonder farewell to Mr Barringer. I felt as if I were standing on the wharf, and that the passengers I’d met along the way had ridden away from me to their new lives without bidding farewell. We had, after all, been on a long journey together.

Source: Review copy courtesy National Library of Australia publishing.

I have posted this review to the Australian Women Writers Challenge 2016.

Immigration is a topic I come back to, over and over again. And it really doesn’t matter too much if the travellers were convicts dragged out in chains, voluntary immigrants looking for a better life, oppressed refugees from a racist, right wing government or asylum seekers who somehow survived their homes and cities being bombed into rubble. They were never really wanted here:

http://melbourneblogger.blogspot.com.au/2012/09/evian-conference-on-refugees-july-1938.html

In my generation, the story was the same. In 1953 my school was packed with refugee families, taken from U.N displaced persons camps across Europe. The children were born in Europe in 1947-8, so although the parents may have hated the trip, the children were too young to care.

Had my father in law travelled to Australia alone, he would have been placed in a long row of bunk beds with the other men. But because he came with a wife and three children, they were given a cabin. Squishy yes, but at least it was just for the five of them!

I was also surprised to learn of the emigration depots back in England which was simulation of the steerage experience, with emigrants forced to sleep in dormitories to familiarise them with the life that faced them at sea. It couldn’t make up for the sense of loss saying goodbye to home and family, for ever. But it could prepare them A BIT for their future.

LOL Janine, from my experience of shipboard travel from England to Africa and four years later from Africa to Australia – that’s exactly what does happen: people do ride “away to their new lives without bidding farewell”. We had two long voyages of four weeks, (and one of shorter duration from city to city along the coast of Africa) long enough for both adults and children to establish friendships – but in the hustle and bustle of getting ready for the new life, all that is forgotten….

Thanks. Asking my local library to buy a copy.

Pingback: This Week in Port Phillip 1841: 1-7 March 1841 | The Resident Judge of Port Phillip

I have just recently been exploring the immigration journey of one poor family from northern England to Brisbane in the 1870s. I agree that there is so much family historians could dig up about the ship board journey. The family I was tracing did not document their journey but I could recover a good amount of detail from the report of the captain at the end of the journey, the passenger list, various newspaper articles etc – much more than I expected. Thanks for reviewing this book. I’ll keep it in mind.

Pingback: This Week in Port Phillip 1841: 16-23 March 1841 | The Resident Judge of Port Phillip