2013, 231 p & notes

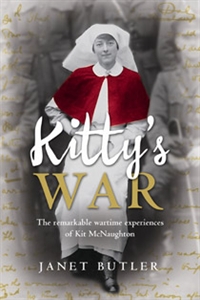

KITTY’S WAR by Janet Butler

I had forgotten the power of a beautifully written introduction to a history.

Imagine, for a moment, that we are granted an eagle’s eye-view of the fields and villages, the roads and towns of northern France. It is dusk on a mid-autumn evening. This is the Western Front, one hundred and eighteen days after the beginning of Operations on the Somme…. (p. 1)

Sister Kit McNaughton was a nurse from Little River, near Geelong who heeded the call for nurses during the First World War. As did many others, she wrote a diary and this book, by Janet Butler presents extracts from that diary. But Butler here is not an editor, stepping to the side to allow the diary and the diarist’s voice to take centre stage (as, for example, Bev Roberts has done in Miss D. And Miss N.) Instead, Janet Butler interrogates the diaries: she triangulates them against other writing; she supplements them with secondary sources; she looks for patterns and changes over time and she listens to the silences. Kitty’s own (rather prosaic) entries take up a small proportion of the book – perhaps ¼ of the text, if that. The majority of the text is the historian at work, always respectful of Kit McNaughton and privileging her perspective, but grappling with the diary as text and the emotional and physical enormity of the unfolding experience that it documents as well.

A diary fills multiple and often changing purposes. The writer often has an audience in mind: sometimes explicit (as in Anne Frank’s ‘Kitty’) or sometimes unnamed but tacitly understood. As Butler writes about Kit McNaughton’s diary:

There is clearly a ‘you’ addressed in its pages. ‘We often think of the people at home & wonder what you are all doing,’ she writes after describing a concert given by the troops, the first day out of Australian waters, ‘& if you could only see us all doing the grand you would know how we are enjoying our selves’. It is to this audience that Kit’s presentation of herself has to be acceptable. (p. 13)

Kit conceives her writing as a travel diary, but she also is conscious that she is chronicling history as well.

…Kit’s diary intersects briefly, under the umbrella of the travel diary, with another kind of diary: the public chronicle of an historic event, which is more often than not a male prerogative (p. 27)

Kit McNaughton is aware that she is writing for an Australian audience ‘at home’ who will read her diary with a particular consciousness: they will want to see her as the ‘good nurse’ imbued with the discipline, rigour, efficiency and obedience of her professional calling; they will be sensitive over descriptions of Australian suffering and death; and they will share her sense of Australianness. She draws from the rhetoric of the Anzac legend, already being honed in the despatches of the war correspondents and seized for recruiting purposes at home, as a way of presenting herself. In doing so, she contributes to our own understanding of the legend 100 years later.

Her use of the ANZAC legend to actively craft her persona shows agency. The nurses are not simply passive recipients of the identities thrust upon them. It reveals a desire for a level of freedom denied them at home. For nurses travelling to war, the Anzac legend opens out the boundaries of acceptable behaviour…. They continued the work they did as civilians, but their journey into war challenged and enabled them to expand their sense of self. (p. 18)

The book follows Kit chronologically as she starts off in Egypt, as so many WWI soldiers did; is sent to Lemnos, falls ill and is sent to a convalescent hospital. On going back to Europe, she nurses wounded German soldiers on the Somme, returns to No 2 Australian General Hospital at Trois Abres just six kilometres from the front, goes across to No. 3 Australian Auxiliary Hospital in Dartford, Kent and finally is sent to Sidcup maxilla-facial hospital nearby. Each separate placement has its own chapter in the book, but multiple themes run across them all: her sense of being Australian; the resentment with which the nurses are sometimes greeted either because they are women or Australian or both; her companionship with the ‘boys’ she met up with in Cairo and her friendship with other sisters (in both senses of the word). There is much that she cannot say, however. To complain about the dismissiveness of the doctors would be insubordination (and a ‘good’ nurse is never insubordinate); to speak too much of the death and injury of Australian soldiers is too sensitive. Nursing German soldiers however- the enemy- is different, and here she can write of the injuries and the smell and the loss in a way that she could not when nursing Australian soldiers:

I have eleven with their legs off and a cuple ditto arms & hips & heads galore & the awful smell from the wounds is the limit as this Gas Gangrene is the most awful thing imaginable, a leg goes in a day. I extracted a bullet from a German’s back today, and I enjoyed cutting into him…the bullet is my small treasure, as I hope it saved a life as it was a revolver one (p. 130)

In many ways Kitty understates her own role. As we can see, she was entrusted with the scalpel, and she later worked in the operating theatre and administered anaesthetics- all skills that were denied nurses ‘at home’. She was mentioned in despatches; she won a Royal Red Cross.

But soon the silences are not just evasions and glossing-overs but the actual lack of words. Particularly once she reaches Dartford, her entries become summaries, widely spaced and sparser, reflecting her own “disengagement from the war of which she no longer feels so much a part” (p. 197). Kit is no longer on her journey, and she is no longer writing a travel diary. There is no adventure, no sightseeing (which she had earlier managed to do), and Butler suggests that she is probably suffering what we would call post-traumatic stress. Certainly, her photographs show that the war has taken its toll on her. Her hair has gone grey; she has lost two stone; she is in poor health.

As Butler says:

Statistics alone cannot provide a guide to the impact of war on personal lives. Our journey with Kit has shown biography to be a way of reaching to the level of the personal and private. Stepping beside Kit, an individual, into the aftermath of her war- reading her life, as we once read her diary- offers the possibility of insight into the effects on women, on the relationships between women and men, and therefore on Australian society, that more objective measures cannot. (p. 216).

The book is written in the present tense throughout. I must admit that I’m rather ambivalent about the use of the present tense in fiction because it makes me feel edgy and anxious. (Says she who has written this whole review in the present tense!) It’s an interesting and striking choice in non-fiction, and one that I haven’t seen used often in history. I’m not quite sure how I feel about it. It makes me feel edgy here too, just as it does when it is used in fiction, but it certainly has its strengths as well. It brings the intellectual and emotional interrogation of the diary right onto centre stage, and Butler’s frequent use of “we” draws you, as reader, into engagement with the diary as well.

“Kitty’s War’ is a reverent and sensitive tribute to Kit McNaughton. It’s much more than a platform for making her diary available to a wider audience. It shows the historian at work, shuttling between the small detail and wider overarching questions of gender, war, personal identity, Australian identity and the ANZAC legend.

You can read Lisa Hill’s review of this book at ANZLitLovers and Yvonne Perkins has reviewed it at Stumbling Through the Past. You can also read Janet’s own guest post about writing the book on a nursing blog.

I have posted this review as part of the 2013 Australian Women Writers Challenge.

I’m so glad you admired this book too! I honestly think it’s the best ‘war book’ I’ve ever read, and (I know, you might not believe this, but it *is* true), my husband and I were talking about it *again* just last night. I think it’s because it’s a book that has taught me to think like an historian that it keeps cropping up in our conversations:)

Kitty’s War is a well-crafted book and you have done a great job of reviewing it. Your observations of the use of the present tense are interesting. I wonder if the use of the present tense helped me to feel more absorbed in the book as if I was part of it?

Possibly- it did make you feel as if you were doing the analysis yourself (even though, of course, it was Janet Butler doing the hard yards!)

Pingback: ‘HHhH’ by Laurent Binet | The Resident Judge of Port Phillip

Pingback: Histories, Biographies, Memoirs – Roundup #7 2013 | Australian Women Writers Challenge

Pingback: Janet Butler – Kitty’s War…. Book Review | Freud in Oceania

Pingback: Histories, Biographies, Memoirs – Roundup #10 2013 | Australian Women Writers Challenge

Pingback: Australian Women Writers Challenge 2013 completed! | The Resident Judge of Port Phillip

Pingback: Histories and Life Writing in 2013 | Australian Women Writers Challenge

Pingback: The War That Changed Us | The Resident Judge of Port Phillip

Pingback: ‘Australians at Home: World War I’ by Michael McKernan | The Resident Judge of Port Phillip

Pingback: ‘Red Cross Rose’ by Sandra Venn-Brown | The Resident Judge of Port Phillip