BIG NEWS! THE OPENING OF THE SUPREME COURT 12 APRIL 1841

The opening of the Supreme Court in Melbourne WAS big news- not just for this blog (which is named for the First Resident Judge of the District of Port Phillip) but for Port Phillip itself. The creation of a permanent branch of the Supreme Court of New South Wales in Melbourne (as distinct from a regular circuit court) was both a way of marking the significance of the district, and also solving a personnel problem for Governor Gipps who was having to deal with conflict amongst the judges on the bench when they were all together. In a practical sense, it meant that substantial civil cases could be heard in Melbourne rather than the parties travelling up to Sydney, and that criminal cases no longer had to wait in jail until there was a sufficiently large number of prisoners to be escorted by ship to the Supreme Court in Sydney. From a community and social point of view, it meant that barristers and other professionals would be attracted to the Port Phillip district, and that there was a focus for public and political discourse.

I hadn’t realized previously that Good Friday was on April 9 in 1841 and that therefore the court opened immediately after Easter. Devout Melbournians could have had a glimpse of their new judge in all his regalia on the preceding Sunday, because he and Edward Brewster had attended church at St James’ Church of England in their legal robes. The other ‘gentlemen of the long robe’ must have wished that they were wearing theirs too, but they were not.

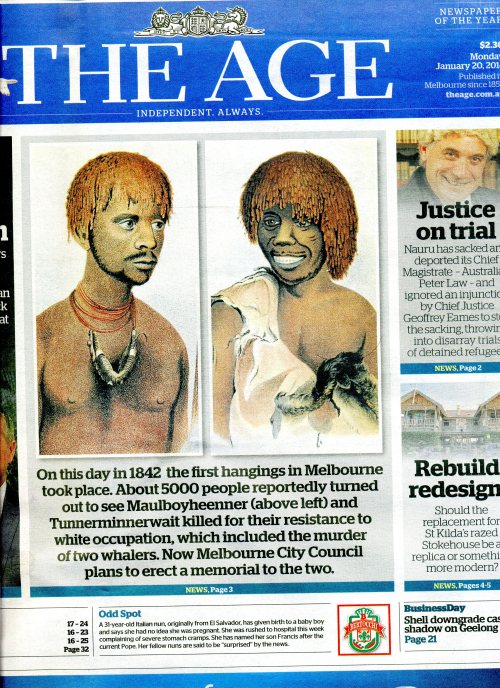

The court opened at 10.00 a.m. on what we would know as Easter Monday in the small building that had been repurposed from its former incarnation as a Works building.

William Liardet, ‘The Opening of the Supreme Court’. State Library of Victoria (www.slv.vic.gov.au)

The Clerk of the Court read the Queen’s Proclamation for the Suppression of Vice to open the court. He then read the Queen’s Commission appointing Willis as a judge, followed by Governor Gipps’ proclamation appointing a judge to the Port Phillip District, then finally Willis’ commission from Gipps that appointed him to the position. After taking the oath, Willis then swore in James Raymond as Sheriff and James Croke as Crown Prosecutor. He then admitted five gentlemen to the bar: Croke, Brewster, Barry, Holme and Cunningham.

I’ve written about the opening of the Supreme Court previously, so I won’t repeat it here. But, I will give you a little taste of Judge Willis’ opening speech, which both captured the essence of his in-court persona and also foreshadowed his dismissal just over two-and-a-half years later:

I am well aware, however, of the peculiar position of a sole presiding judge, and more especially of his liability to the suspicion of local prejudices and partialities. I have always been of opinion with a learned writer “that the less local connexion a judge may have with the place in which he exercises his jurisdiction, the more he will be exempt from the unconscious and danger influence of any collateral motives; and that even being a stranger in a particular set of advocates, otherwise than by the general intercourse of the profession, has a favourable influence on the administration of justice. Particular partialities may exist, and are much more frequently imputed, among those with whom there is a regular and constant intercourse; and although no person worthy of a judicial appointment, will purposely and knowingly act in opposition to his duty, it is certain that habits are said to have arisen of some individual with greater attention and complacency than others, and thus to have induced a feeling of freedom, and even dictatorial familiarity in the one case, and of oppression and embarrassment detrimental to the interests of justice on the other.” (See letter from Sir. W. D. Evans, late Recorder of Bombay to Lord Redesdale, anno 1812).

Lord Brougham in his speech in the House of Commons in 1823, on the administration of the law in Ireland, thus addressed himself “that if a judge be bound at all times to maintain the dignity of his exalted office; if partiality be the very essence of judicial duty, and without which no judge can be worthy of the name- any mixture in party dissensions- any partnership in religious or political disputes- anything like entering into the detail of class difference and arrangements- anything approaching, however distantly, the tool of a particular faction would be a sort of stain from which above all others the Ermine ought most immediately be purged and cleaned. For 1st; such interference touches a judge’s dignity; 2ndly, it renders his impartiality suspicious; and 3rdly, it goes to shake that respect which is due to every just and dignified magistrate, that respect, which if a magistrate forfeit by his misconduct, the sooner he vacates his office the better; the sooner the balance is wrested from him which he can no longer be expected to hold fairly- the sooner he drops the sword, which none will give him credit for wielding usefully- the better for the community and the law. When once he has rendered it impossible for the public to view him with confidence and respect, he cannot too soon lay down an authority the mere insignia of which are entitled to veneration.”

I thus candidly avow my knowledge of the dangers to which a Resident Judge is exposed, and I do so, trusting that this knowledge will enable me to avoid them. But should the Resident Judge of this district ever afford just cause of suspicion, or complaint, the act whence he derives his authority by enabling his Excellency the Governor from time to time to appoint one of the judges of New South Wales to reside within this district provides an effectual remedy for any of the evils incident in this office.

The speechifying and swearing-in over, the court began hearing cases. In this inaugural sitting, there were three cases: two of stealing and one of embezzlement. All were found guilty.

And so this year (2016), the Supreme Court in Victoria is celebrating its Dodransbicentenary (now there’s a term to conjure with!) Strictly speaking, it was still the Supreme Court of New South Wales, but it was the start of the Supreme Court in what was to become Victoria. It was such a big occasion that I’ll just let it sit here, dominating the events of the week 8-14th April. Happy Dodransbicentenary, Supreme Court!